Biography

Bio – Unveiling the Empowering Legacy of Black Karate: A Cultural Movement Blending Martial Arts with Community Building and Holistic Education in Chicago’s Ghetto, Fostering Pride and Empowerment Through a Unique Blend of Self-Defense and Cultural Heritage.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Russell Meek’s Dravidian School of Self Defense in Chicago’s ghetto combined karate with subjects like languages and mathematics to foster community pride and self-defense. This movement reinterpreted martial arts history to connect it with African-American heritage.

Black Karate in the Chicago Ghetto: A Story of Community, Pride, and Self-Defense

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a unique and powerful movement emerged in the Chicago ghetto, centered around the practice of what was termed “Black Karate.” This movement, led by figures like Russell Meek, was not just about martial arts; it was a multifaceted effort to build community, instill pride, and provide a comprehensive system of self-defense and personal development.

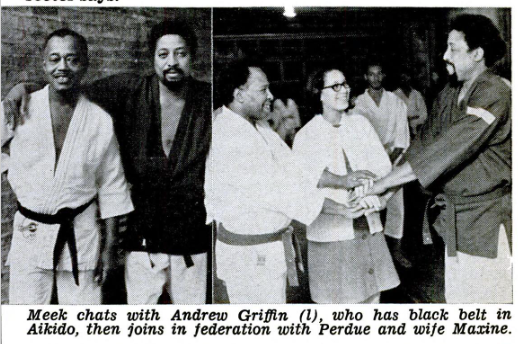

Russell Meek, a media personality, lecturer, and civil rights advocate, founded the Dravidian School of Self Defense in Chicago. Meek’s approach to karate was distinct, as he blended traditional self-defense training with additional subjects such as foreign languages (Spanish and Swahili), mathematics, and music. This holistic approach was designed to support racial pride and success in the challenging environment of the Chicago ghetto.

Meek’s school, located in a former greenhouse and florist’s shop, offered classes that were both gender-segregated and mixed. Female students played a crucial role, often serving as assistant instructors and leading classes. The curriculum emphasized mental discipline, character building, and the integration of physical and mental well-being. Students were taught to embody “outer hardness and inner peace,” reflecting the principles of yin and yang and the concept of wu-wei, or spontaneous and natural action[1].

The narrative behind Meek’s Black Karate was deeply rooted in a reinterpreted history that linked African-American heritage to the origins of martial arts. Meek promoted the theory that the Dravidian linguistic and ethnic groups of Southern India, who were believed to be descended from African immigrants, had brought martial arts to Asia. This narrative served to reclaim martial arts as a part of African-American cultural heritage, making the practice more meaningful and socially attractive to potential students[1].

Despite financial struggles, the Dravidian School gained prominence and became a charter member of the Black Hwa Rang Do Martial Arts Federation. The school’s impact extended beyond physical training, as it addressed the broader social and economic challenges faced by African-Americans in the ghetto. Students learned not only how to defend themselves but also how to cope with the systemic threats and frustrations of their environment[1].

The timing of this movement coincided with a broader cultural shift. The late 1960s and early 1970s saw a growing interest in Chinese and Asian martial arts in the United States, which was later amplified by the popularity of Bruce Lee’s films. However, the Black Karate movement predated Lee’s rise to fame and was part of a larger trend where martial arts were adapted to address community-specific needs and social issues[1].

Recent Developments and Continuing Impact

In recent years, the legacy of the Black Karate movement continues to influence martial arts and community development. Here are a few key developments:

Community Engagement and Empowerment

Modern martial arts programs, especially those in urban areas, often follow in the footsteps of Meek’s holistic approach. These programs integrate physical training with educational and cultural activities to empower youth and adults. Organizations such as the Black Belt Masters in Chicago and similar initiatives across the U.S. continue to use martial arts as a tool for community building and social empowerment.

Cultural Reinterpretation and Appropriation

The concept of reinterpreting martial arts history to align with local cultural narratives remains a significant aspect of martial arts studies. This phenomenon is observed in various global contexts where communities adapt and localize martial arts practices to reflect their own histories and identities. For example, in some African-American martial arts schools, the emphasis on African roots and contributions to global martial arts continues to be a powerful motivator and source of pride.

Gender Inclusion and Leadership

The role of women in martial arts has evolved significantly since the days of the Dravidian School. Today, women are not only active participants but also leaders in many martial arts organizations. The inclusive ethos of Meek’s school, where women served as instructors and led classes, has become a model for modern martial arts schools that emphasize gender equality and empowerment.

Financial Sustainability and Community Support

One of the challenges faced by the Dravidian School was financial sustainability. Modern martial arts programs often rely on a mix of student fees, donations, and community support to operate. The importance of financial stability is underscored by programs that seek to maintain long-term viability while continuing to serve their communities.

Conclusion

The Black Karate movement in the Chicago ghetto during the late 1960s and early 1970s was a pivotal moment in the history of martial arts in the United States. It exemplified how martial arts could be adapted to serve as a tool for community building, self-defense, and cultural empowerment. As martial arts continue to evolve and spread globally, the lessons from this movement remain relevant, highlighting the importance of holistic training, community engagement, and cultural reinterpretation.